Overview of the letters in Section 2 (each of us volunteered to summarize one subsection):

Disruption of Affairs - questions of chronology arose in this section because some letters were not dated

Shameful Concubinage - focus on daughters in this section; interesting references to conception of children as significant; often those making the petition were fathers

Dishonor of Waywardness - tbd

Domestic Violence section - focused on theft; few cases of parents complaining against daughter (so case on p. 205 of suicidal daughter stands out)

Bad Apprentices - similar theme of sons being sent to apprenticeships and becoming drunks and libertines

Exiles - the punishment does not seem proportional to the behavior

Fam Honor - this section is mostly women; direct appeals to honor

Parental Ethos I - all arrestees in this section were male; the direction of the appeals is not always clear.

Parental Ethos II - tbd

Throughout sections, the theme presented in the section headings didn't seem to differentiate these letters from those in other sections. Also striking was the ages of the children (early to late 20s), which raises questions of dividing line between adulthood and childhood.

Discussion of Letters and Foucault's Introductory Texts:

Questions:

Why do they organize the archival material into subsections?

How does one tease out the prevalence of a certain style of justification in these letters, given that others exist? Why do some of these become organizing principles for compiling and organizing the letters?

Discussion:

Foucault's discussion of the shift from 1728 to 1758 (135ff.) is interesting (from affection to education); very Foucauldian attention to shifts (did not appear in previous section).

The two introductions are clearly written by two different people. Are the two introductions reflective of two different historiographical approaches? "Tableaus of conjugal life" (29) v. "existence of a model, a framework" (135) in a process of "evolution". Social groups v. historical differentiation (135).

What is at stake in organizing concepts like "threshold"? How does one locate a distinction in an archive? Why not theorize those "thresholds" as proper places in their own right?

How is Fouc's introduction functioning?

Thursday, January 25, 2018

Thursday, January 18, 2018

Foucault & Farge, Disorderly Families, I. Marital Discord

Thursday Jan.18, 2018

Questions

· * Emergence of terms (e.g. ‘madness,’ ‘debauchery,’

etc.) – relation between scribes & formalities of language of the lettres de cachet – who is determining

the language used in letters?

· * Do scribes literally transcribe what the

subjects are saying, or are they just compiled from notes?

· * How might we categorize medium in a Foucauldian

vocabulary? Is strategizing coupled with classification in a Foucauldian vocab?

(p.43)

· * Unpack the method of reading deployed here (e.g.

“surface of the couple” p.32-3)

· * Theme of repentance and relation of theme

through history of punitive practice (p.47) How clearly do these claims connect

to MF’s narrative histories of punishment? Emergence of the social attitude of

repentance – as cause for disciplinary punishment? (p.48)

· * How does gender map onto the organization of the

letters?

Responses

Method of reading

– how are they describing the reading on p.32? – What emerges from the reading

of these petitions? – interlaced systems of values? Surface – why use this

language? Is there a depth? Does the order of importance come from untangling

this system of values? Is it found within the genre of the writing?

What is the difference between the visible & the surface

that comes into view from the gaze of the others? (see also p.42) – Surfaces &

visibilities à

bringing a positivity into view

Reading method à collecting letters;

historiographical question of how one assembles the visbilities/positivities –

what is the empirical status of MF’s work? Positivities as facts. MF’s positivism

Positivities taking on different significance than those in D&P, where they have an added layer

of interpretation/analysis?

Reading for themes? Are they reading for the themes?

Reading as a question of seeing/visibility*

Documents that make visibilities sayable

Is this function of archival material or function of

private/public distinction or function of both?

Private life enigmatic to neighbors/to public.

Letters – mechanism by which their private life gets made

public – obscure lives make public this otherwise private concern

What is meant by public & private here? Public – known by

authorities (police)? Because they were known by others?

Public/Private – public determined by the limits of the

sovereign – private, what is lost

Private – what gets lost, what is obscure? Public – what becomes

visible? What is visible?

Politics of the family – gendering of public/private (p.48-9)

letters prior to reified gendering of the split between the private/public * (Both

husband/wife make these petitions)

What belongs to genre of letter-writing – where the

discourse comes from that is used in the letters? Categories belonging to the

genre? Do they correspond with categories used by different genres (e.g. court

proceedings, letters written by neighbors)

Imprecision as the medium through which the 18th

century police worked (p.43) – Why is imprecision a medium rather than a

strategy or a technique? Notion of the imprecise police à imprecision = substance

in which the police works because sovereign power is also imprecise

Police not generating the stakes (or the categories) of the

practice, but are reactive.

Thursday, January 11, 2018

Farge & Foucault, Disorderly Families, Introduction and Afterword

Introduction and Afterword:

Disorderly Families

1. Can we discuss the representativeness of the

sample? (pg. 27). Found it surprising that they picked two years. Interesting

archival choice. Why did they pick the two years?

2. What do we make of the

attention to affect in the afterword - specifically, how is affect influencing

how they read the archive and how they interpret it (especially the technique

of copying as creating a kind of intimacy between Farge, Foucault, and the

lives they are reading about) (pg. 269-270)?

3. Why did they write a book

that is largely just the reproduction of archival material?

4. Can we discuss these

sense of construction implied in the "greats" constructing systems designed

to dismiss common people? (pg. 268)

5. Is the function of the

text as a presentation of archives different from the function of a text like Discipline and Punish?

"This is where this

register's paradox lies: it freezes the lives of people quite suddenly, yet at

the same time a feeling of incessant movement, of constant circulation, escapes

from it" (pg. 22).

There is a freezing of the

fugitive world - one of incessant movement. The archive doubles this freezing/movement.

What is modest means? What

does it mean that families were paying to have family members imprisoned? What

are these letters really for? What function do they serve? The aristocracy did

not write these kinds of letters. These letters fly in the face of common

interpretations of French history in terms of the relation between the

sovereign and the people.

These letters reveal

previously unknown lives — rendering singular lives part of history. But how do

we connect this with Foucault's other projects? An ethical gesture - a way of presenting the

archives in a way that leaves the archives open. This might be why the

periodization matters - a way of tending to the shift from sovereign to

disciplinary power without specifically referencing it (he does end up making

it explicit in some other passages - 130 and 260). Repentance emerges as a

theme that marks the shift from sovereignty to discipline (technique of

correction). On 24, the family ends up reflecting the relationships of

sovereign power while being embedded in a host of other relationships.

Is there a lack of

periodization in the piece overall? What would a history have looked like? Why

didn't they pick middle dates? Why not 1743? Self-evident affect positioned

against quantitative representativeness - how is the archivist implicated in

such a project? How is the archivist implicated in the reproduction of archival

material? The practice of writing history seems like an important theme of the

text - experiment with different ways of writing history. These different

practices of writing performs different kind work. There is a spirit of experimentation

at work. If we think of the archives as the writing of history and the

uncovered lives coming into contact with power as the writing of history, this

another way of performing that very writing (in the style of the original). D&P does not perform the writing of

the panopticon, but this piece does perform the writing of the dossiers - an

artistic style. Is it artistic or is it an aesthetic positivity? What does the

experiment consist of? It is an interesting experiment to just reproduce it. "Drawing

an intricate portrait" (268) as an aesthetic that differs from a more theoretical-historical

account - (271) "Foucault saw a tableau where misery would challenge

glory."

Some of the archival

documents where difficult to read and there is an interpretative element

involved in puzzling them together. Does the archive speak for itself? Can we

make a distinction between the archive speaking for itself and it doing something

on its own? For Foucault, the archive doesn't speak for itself in the sense

that it tells us how it should be read. But there are facts that do things for

themselves within the world of the archive (there is a positivity to them).

There is an interesting tension between the sublime nature of the lives (a

politics from below) and the positivity of documenting a form of power. There

is affective tension in the text that has an impact on how they present the

material (suffering-tragedy-intimacy).

Is the practice of reading,

assembling, writing the archive here the same as that in D&P - He seems to reverse engineer the practice of reading in

the Lives of Dangerous Men. The texts

make an ethical claim on him that he doesn't talk about in terms of his earlier

texts based on archives - from the same archive, he is excavating different

projects and the writing is very different. How do we treat these letters

differently from how they were treated when they were written? Emotion informs

from the practice reading the archives for Farge.

Wednesday, January 10, 2018

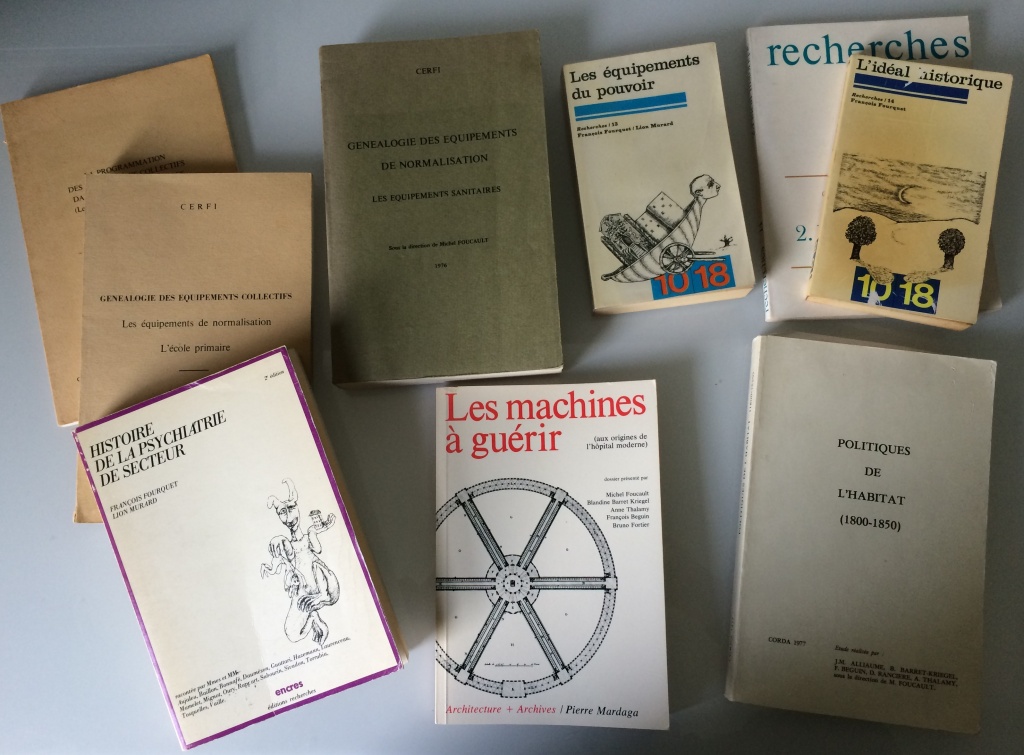

A List of Foucault's Collaborations

Stuart Elden (one of the most diligent and insightful Foucault scholars working today) has a useful overview of some of Foucault's collaborative projects that may be of use to us this term and next. (Thanks to Nicolae for the link.)

https://progressivegeographies.com/resources/foucault-resources/foucaults-collaborative-projects/

https://progressivegeographies.com/resources/foucault-resources/foucaults-collaborative-projects/

Monday, January 8, 2018

Winter Term 2018 Schedule

Continuing our theme for the year, on collaboration, we'll be reading the Disorderly Families project produced together by Arlette Farge and Michel Foucault. All meetings in Leona Tyler Conference Room off of the Graduate Student Lounge unless otherwise marked.

Thur 1/11 - Introduction (AF/MF), and Afterword (AF)

Thur 1/18 - Introduction to "Husbands and Wives" (AF), plus everyone read one section of letters

Thur 1/25 - Introduction to "Parents and Childrens" (MF), plus everyone read one section of letters

Thur 2/1 (location: Allen 332) - "When Adressing the King" (AF/MF)

Thur 2/8 (location: Allen 332)- Farge, Fragile Lives, pp 1-42

Thur 2/15 - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp 42-72

Thur 2/22 - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp. 169-204

Thur 3/1 (location tbd) - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp. 204-256

Thur 3/9 - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp. 256-287 (Ch. 10 and Conclusion)

Thur 3/15 - TBD, perhaps Foucault's "Lives of Infamous Men"?

Thur 1/11 - Introduction (AF/MF), and Afterword (AF)

Thur 1/18 - Introduction to "Husbands and Wives" (AF), plus everyone read one section of letters

Thur 1/25 - Introduction to "Parents and Childrens" (MF), plus everyone read one section of letters

Thur 2/1 (location: Allen 332) - "When Adressing the King" (AF/MF)

Thur 2/8 (location: Allen 332)- Farge, Fragile Lives, pp 1-42

Thur 2/15 - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp 42-72

Thur 2/22 - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp. 169-204

Thur 3/1 (location tbd) - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp. 204-256

Thur 3/9 - Farge, Fragile Lives, pp. 256-287 (Ch. 10 and Conclusion)

Thur 3/15 - TBD, perhaps Foucault's "Lives of Infamous Men"?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)